Finding lost films in modern times – Chai Yee Wei gets real about film restoration

Posted by admin_mocha | Behind the scenes, Feature posts | No CommentsOur Founder & CEO, Yee Wei, recently attended a prestigious Film Restoration Summer School in the beautiful city of Bologna, in which 46 filmmakers from 36 countries gathered for one single purpose – to preserve our film history for future generations.

Organised once every two years by prominent film archives Cineteca di Bologna and L’Immagine Ritrovata, a world-renowned film restoration and conservation laboratory responsible for some of the most difficult film restoration projects in our time, the training programme allowed its participants to delve deep into the film restoration process, learning about the past and future of cinema from some of the industry’s finest.

As luck would have it, the summer school also coincided with the annual international congress of Fédération Internationale des Archives de Film (FIAF) and Il Cinema Ritrovato festival, in its 30th edition, where Yee Wei had the privilege of experiencing many films that were once considered lost, screened at their best. Shoulders were rubbed and ideas were exchanged, with some of the world’s best historians, archivists, critics and fellow filmmakers in its attendance.

Suffice to say, it was three glorious weeks of cinephile heaven that left Yee Wei more inspired than ever. In his own words:

My perspective of film as a medium has been forever changed.

Read on as Yee Wei gets real about film restoration, with newfound insights fresh from his time in Bologna, and why it’s an increasingly important art in today’s digital landscape.

Film, like time, waits for no one

From the moment a physical print or negative is developed and processed, it will almost immediately begin to decay, shrink and eventually fade away. Nitrate and acetate films can last hundreds of years under extremely strict temperature and humidity conditions (nitrate prints have to be stored in 4°C and 30-40% relative humidity for optimal preservation), but even the best conditions can only slow down the degradation process, and not prevent it entirely.

While polyester films were introduced in the mid 50s — replacing its nitrate and acetate counterparts for its increased stability — it can decay even faster when not properly taken care of, with a lifespan as short as 8 years.

And the sad truth is that any restoration can only be as good as how much you can retrieve from a decayed print or negative.

The harsh realities of film preservation in Singapore

Singapore is known for many things, of which our “endless summer” comes to mind, with relentless heat waves often well above 30°C and a relative humidity of 90% all year round.

We’re also increasingly known for our growing crop of homegrown filmmakers — the likes of Eric Khoo, Royston Tan and Boo Junfeng, among others — whose films have found recognition both locally and overseas, putting our little red dot proudly on the map.

Yet, when you put those two together, it’s befuddling that we don’t even have a proper film vault dedicated to preserving our own film history.

While the Asian Film Archive — Singapore’s only repository for film and tape which turned a decade last year — has been religiously providing refuge for Southeast Asia’s rich film heritage; their prints are stored in vaults designed for paper prints and other forms of media with an average temperature of 18°C, a far cry from what film prints require.

In fact, 80% of the prints currently held by the archive are now suffering from “vinegar syndrome”, a nasty little pickle commonly faced by “infected” prints that decay at a faster rate when kept together, even in a controlled vault.

A scene from Eric Khoo’s Mee Pok Man (1995) restored by Mocha Chai Laboratories using the original 35mm camera and sound negatives at L’immagine Ritrovata. It was screened at Singapore International Film Festival in 2015, two decades after its inception.

Did you know that we came this close to losing the prints of Eric Khoo’s 90s classics, Mee Pok Man (1995) and 12 Storeys (1997), which survived only because they were recovered from overseas? Imagine that.

If you think a preservation copy on tape is good enough, think again. Even the high quality and clarity of 4K is limited when it comes to representing the grain on film. At the end of the day, we still need to preserve the negative or print in its best possible state so that — as better technology comes along — we can achieve better restoration.

Keeping cinema alive through film restoration

To understand the purpose of restoration, we need to first understand “what is cinema?”

Cinema is the telling of stories with moving images and the consumption by an audience.

In itself, cinema has changed throughout the years, and will keep changing based on improvements in technology and shifting trends in how it is consumed. As the Greeks once philosophised – the only constant is change itself.

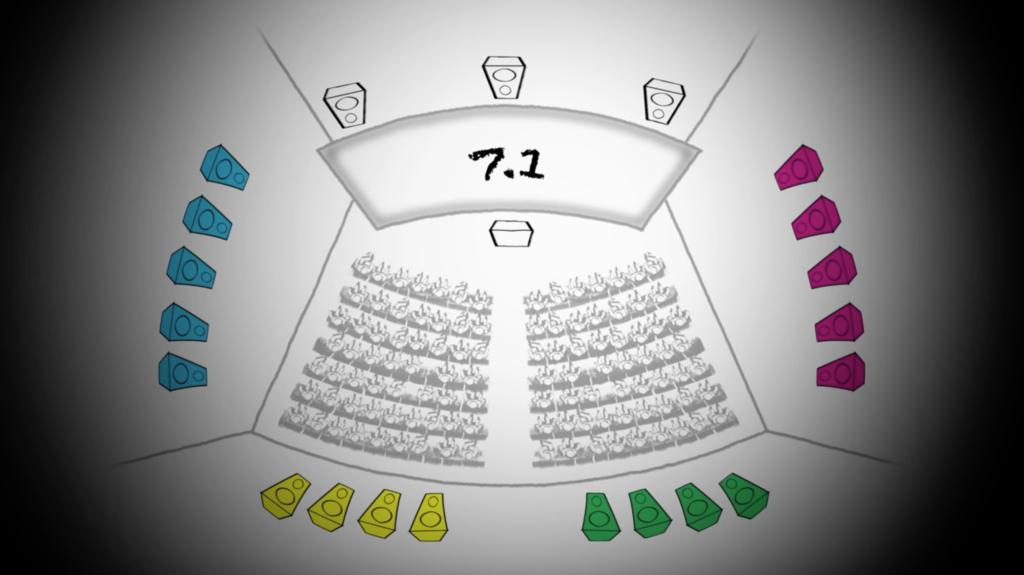

When we look to preserved copies of film for restoration, it is often for one of two reasons – because we don’t have the tools to view them, or there are easier or better ways to present them. You’ll be hard pressed to find a functioning film projector in most countries these days, and the only way we can view some old 16mm or 35mm prints is to move them from older carriers to new ones such as DCP (Digital Cinema Package).

Likewise, when the time comes for newer standards to replace DCPs, we will have to migrate the content to new carriers and containers.

Film restoration, however, is more than just moving the content from one carrier to another. The content itself may have been warped and degraded, leaving behind marred images with lost colour, scratched pictures, or in the worst cases, frames or sequences get lost. Rather than a simple scanning and screening, film restoration represents the extra effort required to recreate the original content, if even possible at all.

But let’s be clear about one thing: no restoration will be possible, if no prints survives.

Chillingly similar to climate change, if there is no will of mankind to preserve the celluloid, the time will come when there is a point of no return. However, unlike climate change, when that happens, there is nothing even the best in the business can do to recover a print that is lost forever. A damaged print cannot magically heal itself.

It doesn’t end with digital

Some might argue that the concept of preservation and restoration is less relevant in today’s digital landscape, where most films are shot and released digitally.

But just take a look at how cinema has evolved over the decades. Film prints have evolved from nitrate to safety prints. 16mm films are duplicated on 35mm negatives for preservation. Data will be moved from PATA HDD to SATA HDD. Spinning discs become solid state; LTO-6 becomes LTO-7; FAT32 becomes NTFS, so on and so forth.

Big, scary technical jargons aside, one thing remains the same – change. It’s been happening all throughout history and we can safely assume technology will not be spared. In fact, technology will only continue to evolve, churning out shiny new tools to help us migrate our digital films. As filmmakers, it is our responsibility to keep up with times and try to preserve the original source as much as we can.

Perhaps a century from now — thanks to our continued efforts in the preservation and restoration of film — our local classics like Mee Pok Man (1995) and Money No Enough (1998) will still be viewable in the cinema of the future exactly as how the directors intended it to be, continuing to inspire a new flock of homegrown filmmakers. But time is not on our side, and it’s imperative that our efforts begin now.

Preserve so we may restore. Restore so we can preserve.

Image credit: Dolby

Image credit: Dolby

Opening day of George Lucas’ Star Wars at Grauman’s Chinese theater, May 25, 1977

Opening day of George Lucas’ Star Wars at Grauman’s Chinese theater, May 25, 1977 Image credit: Dolby Laboratories

Image credit: Dolby Laboratories Image credit: Dolby Laboratories

Image credit: Dolby Laboratories Image credit: Warner Bros.

Image credit: Warner Bros.

Recent Comments